Great Britain Trip: Part 5 - A Green and Magical Land

Great Britain Trip: Part 5 – A Green and Magical Land

Two weeks ago I embarked on my first trip to Europe, specifically to Great Britain. This journey had two aspects. First, it is the closest I’ve had to a vacation in at least four years. But honestly, I don’t really do vacation. The primary reason for the trip was to assist several projects I’m working on, including a volume I’m currently writing on why archaeology has the “spooky” image it has in the public imagination.

The following images are not in precise chronological order, though the general narrative does roughly follow the order of places I visited. I spent four days in London at the beginning and another two at the end, and these materials are something of a chronological jumble for thematic purposes. These images are a fraction (specifically, about 7%) of the images I took. Many of these were for research I am not discussing in depth here, or for teaching purposes. The images and text here are instead a rough tour not so much of where I went as why I went, what I learned, and why that might be of interest.

This travelogue is broken into seven sections

Rule Britannia!

Archaeology of Empire

Mysteries of London

Time in Bath

A Green and Magical Land

Investigating Inverness

The Legend of Loch Ness

A Green and Magical Land

I had chosen to stay in Bath so that I could visit some of the archaeological and other sites in the English countryside of relevance to my work. I decided the most effective way of doing this, and also getting a bit of understanding of how people engage with archaeology and the landscape, was to take a day tour from Bath. I chose (and enjoyed) Mad Max tours, which offers several options including the one I chose, to visit Stonehenge, Avebury, and the medieval villages of Lacock and Castle Comb on the southern edge of the Cotswolds. This was a small group rather than a massive bus, which also had certain advantages, including navigating some of the narrow country lanes.

Stonehenge was the major focus of the morning, though it seemed for many people to be their least favorite part of the day. The oft-cited complaint that one cannot approach the stones, and can only see them from a distance, was commonly voiced. The entire experience was focused on around access. When one arrives at the new visitor’s center, one must then get clearance to get on one of the shuttle buses that take visitors to a drop off point, from which one then approaches the main henge. Most visitors walk around the stones for a bit, maybe listen to the National Trust audio tour, and then get back on the bus back to the small if informative visitor’s center.

Another complaint I heard voiced several times at the site or later was that the monument is in sight of a major road. I am not sure what exactly are visitor expectations to Stonehenge, but I suspect the fame of the site as “something to see” mean that these expectations will never be met in full. For myself, I was pleased at the minimal amount of security and visual clutter between the visitor and the primary monument. The day I visited, this was somewhat marred by the filming of a commercial. At first I thought perhaps a press conference was underway as a large crew with multiple cameras was present along with flanking security. The security officers said this sort of thing was quite rare at the monument.

The importance of the larger landscape of perishable structures and tumuli is repeatedly emphasized in both the visual and audio information, but I don’t think this has much visitor impact. While it appears one can technically walk to these parts of the landscape, without clear pathways, no one did.

One aspect that was repeatedly discussed in both the National Trust’s material and in the tour material by my guide company (which has both a live guide and audio recorded guidance by the head of the company) is that Stonehenge was NOT built by druids. Who the druids was not, to my memory, 100% explained except that they were later and closer to the time of the Roman Conquest, but that the monument itself is older. The National Trust also definitely addressed (and the private tour may have as well, I cannot recall) why druids came to have a romantic appeal with the birth of antiquarianism. This clearly seems to be something of a concern.

The new visitor’s center is small, and the informational section is similar in size to the gift shop, but it is fairly full of artifacts. Many are the stone tools and animal bone remains found at the site. These are used to discuss the history of the larger Salisbury landscape and the henge itself, as well as placing them in a larger context of European prehistory. However, unlike so many other National Trust sites, there are no flashy sculpted monuments, and the most important and richest burials (such as the Stonehenge and Amesbury archers) from the area of Stonehenge are not kept here. Visitors seemed interested in the artifacts, but were primarily interested in the wall display material on the construction of the stone circle itself.

Also popular was the replica stone on a sledge (where visitors could try to pull the stone) and two samples of the type of stone used in the monument. The desire to physically interact with the monument was once again on display here, and I myself have my strongest memory of the site in feeling the texture of the local stone and the Welsh blue stone.

The entire Wiltshire area is dotted with famous prehistoric monuments such as Silbury Hill, West Kennet Barrow, and our next stop at Avebury.

Avebury is the largest prehistoric stone circle in Europe and is not separated from the public as Stonehenge is. This aspect dramatically increased visitor interest and appreciation, even though no significant archaeological information is provided on-site (we did not visit the National Trust facilities here). The engagement with Avebury seems to be largely as an aesthetically impressive and magickal or neopagan site, in contrast to the roped-off and scientific presentation of Stonehenge (I’m trying to minimize how hard I’m hammering my theme here).

Discussion of the stones quickly turned to the sort of folklore that surrounds all the megalithic sites of the British Isles, such as the Devil’s Chair above, or of the fertility powers of the stones.

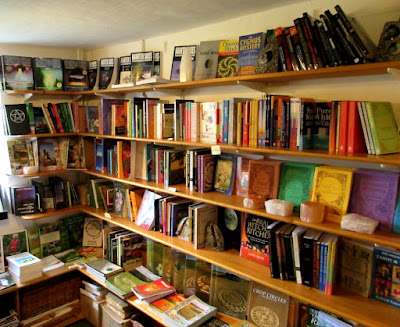

While there is a National Trust center in Avebury, much of the focus of tourism goes to The Henge Shop. While one can buy all sorts of souvenirs here, the primary focus is neopagan and occult materials and literature

On the trip up, discussion of UFOs, haunting, and other strange phenomena was completely intertwined with the archaeological. I didn’t have to look hard to find the “spooky archaeology” theme I was researching. But even I was a bit surprised when our guide pulled out a set of dowsing rods for visitors to try at the site. Avebury is considered a major nexus of ley lines.

The notion of ley lines was first developed by Alfred Watkins in his volume The Old Straight Track. Watkins believed the lines to be ancient sighting or road networks, important but materially mundane. Critics suggested that Watkins was reifying apophenia, creating patterns out of churches, henges, and other spots with no real relation and often separated by centuries or millennia. The development of archaeology out of antiquarianism can be glimpsed in this process. Watkins’ lines are a product of the Ordnance Survey Maps that have played such a key role in archaeological and popular engagement with the British landscape and its antiquity. Yet the mixing of disparate eras into a single “old and special” past smacks of the folkloric approach antiquarians took to the past (the same one that forces the guide information to constantly tell visitors to Stonehenge the place was not built by Druids). These lines are a geographic equivalent of Frazer’s trumpeting of survivals and folkloric understanding of religious prehistory in The Golden Bough.

Even with this criticism, Watkins was still operating in a fairly mundane envelope of reality. Ley Lines did not acquire their supernatural aspect until the 1960s. While this history is a bit murky, the concept seems to derive from ideas that developed very early within the UFO world of “magnetic lines of force” along which UFOs travel. Since then, the notion of surging “dragon energies” and other geomantic concepts of a mystical network or grid have come to play a major role in public understanding of megalithic sites.

Seeing as how my day was simply getting more and more productive, after taking a twirl with the rods, I naturally bought my own set at the Henge Shop.

Our next stop was the historic village of Lacock, an entire town owned and preserved by the National Trust, inhabited by villagers that rent from the Trust. Many of these small communities were at one time owned by wealthy elites, and with the decline of such fortunes, some were acquired lock and stock for preservation purposes. An American comparison might be Williamsburg except that needed to be reconstructed, or living within a state or national park.

Lacock has been used as a set for various films, but the one that seems to attract the most attention is … the use of the abbey to film Harry Potter (is my theme showing?). After a nice lunch in an old pub, we took a drizzly walking tour of the village. One of the highlights of Lacock is the medieval Tithe Barn and Lockup, the center for paying taxes/rent and a small gaol cell. While inside this wonderful timber-frame structure, I noticed something on one of the beams

Let me adjust the contrast

That appears to be a daisy wheel. Some of these may simply be carpenter’s marks, but in other cases they are believed to be apotropaic marks to protect against magic and witchcraft. Visitors to Pennsylvania might compare them with German “hex signs” that may or may not have a magical function. Here are some other examples. Our guide hadn’t noticed this (they’re quite faint as you can see, and the barn is dark), but pointed out stone crosses on some of the slate roofs that served a similar purpose (if anyone knows the technical term for these, please let me know). Here are some other apparent daisy wheels in the tithe barn that I missed.

Likewise, our final stop of the day was the picturesque village of Castle Comb, again used as a traditional backdrop for film productions that want to highlight the cherished image of the pre-industrial English countryside.

I was on my own the following day, taking the bus from Bath to Glastonbury to visit the heart of alternative perspectives on the British past. Glastonbury is steeped in myth and lore. The tor that dominates the town is strongly associated with the Isle of Avalon, the place of healing where King Arthur retreats to convalesce until Britain once again needs him. Glastonbury has been visited by pilgrims in search of healing for centuries and today is strongly centered on magickal, neopagan, New Age, and other alternative residents and visitors. It has a reputation for being a den of aging hippies, and it was the already existing alternative scene that brought the musical festival to Glastonbury.

Downtown Glastonbury has numerous occult stores, New Age healing centers, alternative libraries, eclectic clothiers, vegan cafes, and so on. The Cat and Cauldron, a major supplier of neopagan and magickal working materials, was particularly interesting in its offerings.

Religious icons from around the world rubbed shoulders with antique bottles, bits of animal bone, and other unusual ingredients.

Likewise, traditional archaeological texts sit side-by-side with the works of Kenneth Grant, Crowley, Besant as well as works of self-help, meditation, and fantasy literature

After my time in the British Museum and in the remnants of the Theosophical and Golden Dawn environment in Bloomsbury, this element in a tunnel leading to a neopagan shop, an art gallery, a café, and an alternative library, caught my eye for its use of Egyptian imagery

Back on the High Street, neo-Maya, deep ecology, and scientific imagery combine

Angels and crystal skulls

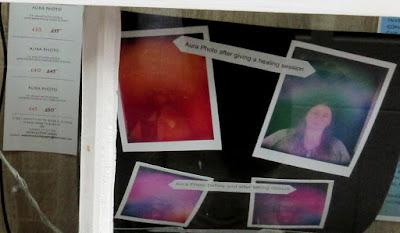

Down one Diagon-esque Alley, you can get your aura read

Or buy some copal

I really don’t have much to say about this next one

At the heart of Glastonbury, and one might argue at the root of modern Glastonbury, is the Abbey. It was the largest abbey in Britain until it was dissolved by Henry VIII.

One of the signature events in its history was the 1191 “discovery” of the graves of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere. Cynics might suggest that the destruction of much of the abbey by fire in 1184, and the subsequent need for major tourist-friendly relics, might have played a role in the successful search for the mythic king.

But this didn’t stop King Edward “Longshanks” I from participating in the re-entombment of Arthur in the Abbey. You may notice an offering left the morning I visited.

One of my reasons for visiting Glastonbury was Frederick Bligh Bond. The Church of England re-acquired the abbey in the early 20th century, and hired noted expert on medieval architecture Bond to conduct archaeological investigations and restore the abbey. However, Bligh Bond is only minimally mentioned in the official visitor’s center today. I wonder why?

Oh, that's why

After he reconstructed the ruins, Bond published the book The Gate of Remembrance in which he revealed his excavations were guided by automatic writing. Using a technique similar to a Ouija board, Bond contacted the spirits of the architects, monks, and neighbors of the Abbey during its years of operations centuries earlier. This isn’t entirely accurate. Bond saw himself conducting an experiment in psychical research and spiritualism, and insisted that rather than participating in a simple spiritualist medium session, he and his compatriot were instead touching a more divine greater consciousness or other entity. Regardless, the Church of England didn’t take this very well, and Bond was fired. He became a minor celebrity in spiritualist and occult circles, but in later years had to pay admission to visit the abbey he had rebuilt.

The controversy swirled in particular around two chapels Bond had “found” with these methods. I had read Bond’s book, but I was in particular luck that day to find a copy of an old guidebook in Labyrinth Books, an esoteric book shop in town. This volume had been written shortly after the controversy, and was sympathetic to Bond.

With my somewhat forbidden guide in hand, I was able to pace out where there the chapels in question were located. One, the Loretto Chapel, got the only “probable” label I saw on site, and was not reconstructed.

The other, the Edgar Chapel, was reconstructed by Bond, but today has no label. It sits behind the tomb of “Arthur.” It is labeled as fraudulent or mythical in some of the more mainstream sources on the Abbey. Myths upon myths. Does this count as a ley line? The wind whipping up and the sky darkening as I entered the spot certainly was atmospheric.

This left the Tor.

Archaeological excavation of the Tor shows occupation going back into the Pleistocene, and remnants of a post-Roman religious settlement can be shoved by the attuned into the medieval myths of Joseph of Arimathea bringing the Holy Grail to Glastonbury.

The spot is spectacular, and provides a spectacular view of the countryside (though the fact that sheep can easily climb the Tor does diminish one’s sense of accomplishment).

I apologize for the length of this particular post, but the Stonehenge, Avebury, Cotswolds, and Glastonbury material is joined not just chronologically in my journey, but thematically in their importance in mythic roots of identity, and engagement with archaeology.

In an upcoming publication, I have written about how so many of the alternatives to science derive from disconnection from control over knowledge. The stale feeling described by so many visitors to Stonehenge is an example of this. The inability to walk amongst the stones makes them just one more glass-cased museum exhibit, like the broken bones and pottery shards that tell a thoroughly scientific tale within (one that repeatedly declares loudly, “And above all, no Druids!”).

By contrast, visitors to Avebury have full control over their engagement with the stones. They may not be aware the stones have mostly been re-placed after centuries of removal. They likely don’t know much about the age of the stones, or what evidence we actually do have to their original use and origin. Instead, all sorts of detritus of the professionalization of science fills the site. Ley Lines. Folklore about fertility and the Devil. Leftover theosophy and spiritualism in the form of UFOs and faerie sightings.

At Glastonbury, the Victorian friction between science and Romantic legend and myth has clearly tilted to the spiritual side of angel energies, workings, and the Holy Grail. Yet despite the meditation chapels and the “exotic” imported faiths brought by the hippies, this is also a place of British myth, of Arthur and healing waters like those in Bath and of a Green and Pleasant Land as Blake put it. Margaret Murray conceived of her witch-cult idea, which is instrumental in the rise of wicca and neopaganism in the 20th century, while on health-related leave in Glastonbury during the Great War. She was inspired by similarities she saw between her professional expertise in Egyptian religion, and the Joseph of Arimathea legend. The Enlightenment-era urban obsession with Egypt as the source of civilization and magical power collided with the English countryside and its folklore, producing a major strain of modern esoteric thought. Bligh Bond’s theosophical-like quasi-spiritualism likewise is a fossil of the late Victorian attempts to re-enchant their industrial world while simultaneously grappling with the deep time of geology, paleontology, and evolution as well as the de-centering cultural diversity recorded by colonial travelers and anthropologists.

But don’t take my word for it. Just go watch Harry Potter and its filming in Lacock, or compare the imagery I’ve been presenting with medievalist Tolkien’s Shire, and see that desire for an alternative green and magical land, one apart from the mundane disenchanted world of industry and change, one thoroughly embedded in an alternative world that never enters yet survives, thrives, and shapes the 21st century.

No comments:

Post a Comment